Reflections from Northwestern University's COP29 Delegation: Day 1

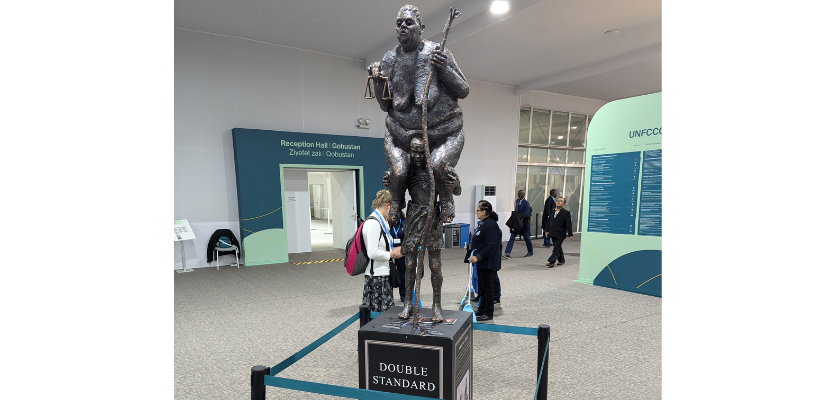

For a fourth year, a delegation of Northwestern University students and faculty supported by the Buffett Institute is among more than 30,000 researchers, policymakers, industry leaders and activists at the world’s largest annual international treaty negotiations and climate summit, the 29th Conference of Parties (COP29) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), this year hosted in Baku, Azerbaijan. Each day, a different Northwestern delegate is blogging about their experiences and reflections. Day 1 features Ezra Danzig, a third-year undergraduate studying environmental engineering and environmental policy.

Until this morning, COP existed only in my mind; a mythical place, where heads of state (and their representatives) from nearly 200 countries gathered to decide the course of humanity’s action on climate change. Despite warnings from the trip leaders, I was still surprised as we walked into the Research and Independent Non-Governmental Organizations (RINGO) briefing this morning. Up until that point, nothing I had seen meshed with the descriptions I had received. I had expected an overwhelmed bus system, infinite lines, impossible site navigation and vendors running out of their overpriced foods. What I got instead was a nearly empty bus, where the four of us got seats together with ease, that got us to the site perfectly on time to wait in a line that simply didn’t exist, leaving us enough free time to get good coffee and excellent breakfast sandwiches from one of the many fully stocked kiosks (admittedly, the overpriced part was still true). So far, COP seemed to line up more with my mental image than the reported reality.

Walking into the RINGO briefing, into the side event room lit by harsh, colorless, bright overhead lights broke the illusion. The arrayed faces of students (mostly), other academics, and associated members of government bodies and NGOs, and the two guiding the briefing – RINGO steering committee members all looked so… normal. When they proceeded to give a veteran’s guide to COP – how to connect with people, find schedules, get tickets, use the printer, and what a select few of the ubiquitous acronyms meant, they sounded… normal, complete with websites not loading, and not being able to find the right buttons.

The day continued to pick apart the illusion, from the never-quite-right climate control, to the technical difficulties with Zoom-ed in presenters who couldn’t be there in person, to the somewhat underwhelming presentations comprising the Earth Information Day 2024—a three-plus hour event in which anyone familiar with climate science and action efforts would have gleaned minimal new information.

Around 5:30 p.m., I found myself sitting in an empty chair at the tables reserved for delegations, which had outlets available, in the main plenary room. The room, intended for the opening plenary session where the agenda would be agreed upon by the parties so the work of actually doing the negotiating could commence, had been in limbo for hours after the opening plenary failed to reach an agreement and was paused, slated to restart at 5:00 p.m. (which it clearly had not) and which was now projected for 6:30 p.m., a time that would inevitably change once more as it was shared by many of the negotiating blocs’ coordination meetings. The lights were the same harsh, colorless white from before. The air was simultaneously too hot and too cold. I was exhausted. These imperfections were not lost on me, but there, in that room, half-full of the fifth- and sixth-in-command from a small fraction of the parties, I was struck by the reality of the place I found myself in. I’ve seen model UN events before, 50 kids sitting in the gymnasium of some suburban high school while some kid who’s never been more than 100 miles from the hospital they were born in represents Kenya in an imagined disaster scenario. Suddenly seeing the room that was based on—hundreds of seats, placards for every country I’d ever heard of (and three or four I hadn’t), four dozen organization acronyms of which I knew maybe 15, and hundreds of people from around the world speaking 40 different languages. It had a majesty and energy to it—still utterly different from my fantasy, but definitely not the banality I had begun to internalize from my mentors.

COP is an imperfect place. It never accomplishes quite as much as people hope. The operations are far from perfect—the green zone ticketing scheme this year seems to have had nightmarish results for accessibility. And the bureaucracy can feel stifling. The power and energy of that first exposure to the reality of the UN—delegates of the nations of the world gathered together face to face is equally real, though. In that moment, the multimodal ethnography made sense as a methodology—that feeling could be data. It was an unfamiliar notion coming from engineering labs; that the energy of a room qualified as an important data point.

If I take away nothing else, I will take away the real COP—a messy, imperfect space full of messy, imperfect people, with an undeniable power.

Photo credits: Ezra Danzig

Ezra Danzig is a third-year undergraduate studying environmental engineering and environmental policy. Since participating in Northwestern University’s 2023 Global Engineering Trek to Chile supported by the Buffett Institute and Trienens Institute, Danzig has been involved in research on mining and sustainable mineral supply chains, including a summer internship with the Sustainable Minerals Institute’s International Centre of Excellence in Santiago, Chile during the summer of 2024. He is interested in the interactions between policy, culture and technology with regards to climate action and the lack thereof.

Ezra Danzig is a third-year undergraduate studying environmental engineering and environmental policy. Since participating in Northwestern University’s 2023 Global Engineering Trek to Chile supported by the Buffett Institute and Trienens Institute, Danzig has been involved in research on mining and sustainable mineral supply chains, including a summer internship with the Sustainable Minerals Institute’s International Centre of Excellence in Santiago, Chile during the summer of 2024. He is interested in the interactions between policy, culture and technology with regards to climate action and the lack thereof.