Reflections from Northwestern University's COP30 Delegation: Day 8

For a fifth year, a delegation of Northwestern University students and faculty supported by the Roberta Buffett Institute is among more than 50,000 researchers, policymakers, industry leaders, and activists at the world’s largest annual international treaty negotiations and climate summit, the 30th Conference of Parties (COP30) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), held this year in Belém, Brazil. Each day, a different Northwestern delegate is blogging about their experiences and reflections. Day 8 features Sarah Lyons, a fourth-year undergraduate studying environmental sciences and political science.

Hello, and welcome to week two of COP30! I am excited to kick off blog posts for the second half of Northwestern’s delegation. My research here at COP30 seeks to understand how Indigenous Peoples are represented at COP and how traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) is incorporated into discussions of policy solutions.

Today was our first day at the conference. The sun rises early here at the equator, and so did we: by 6:30 a.m., I was dressed in 80% humidity-friendly business casual and eating breakfast from last night’s grocery trip (an exciting but slightly harrowing experience which left me seriously wishing that I spoke Portuguese).

Outside the Blue Zone

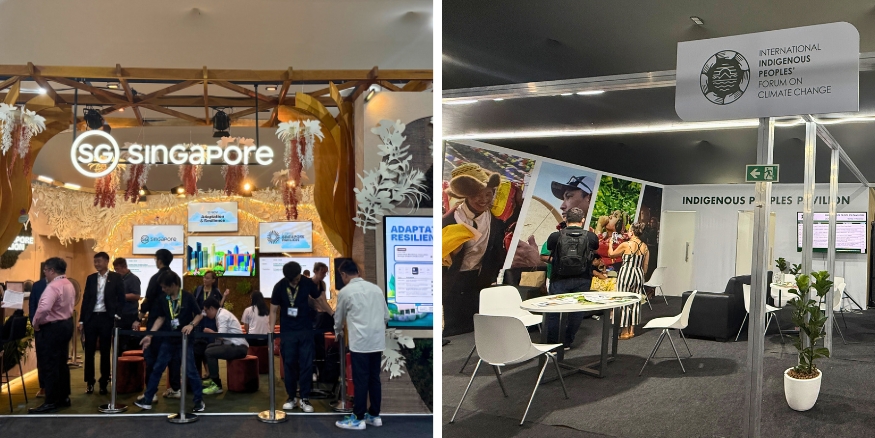

Two hours later, we entered the Blue Zone for the first time. After acquiring my official UNFCCC badge, I began to explore the pavilions. This section of the Blue Zone reminded me of a shopping mall, each pavilion boasting some elaborate display to entice people inside. Brazil’s pavilion, as well as those for countries in Asia and the EU, are the largest and most extravagant—Portugal’s pavilion was reportedly serving wine, while Singapore’s has so many lights and TVs that it resembles a Best Buy—while other countries and organizations are smaller and more secluded. After nearly two hours of searching, I finally found the Indigenous Peoples pavilion in the back corner of a narrow hallway. COP30 has been praised for its unprecedented levels of Indigenous participation, so I found this disparity surprising.

Singapore Pavilion and Indigenous Peoples Pavilion

The first event I attended was a high-level signing ceremony on Indigenous land tenure. Here, the ministers of environment from several countries, including Ecuador, Colombia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, gathered to show their support for the recognition of Indigenous territory. They emphasized that ensuring Indigenous rights and participation is essential for effective climate solutions. Later, I attended a panel discussion on how Indigenous knowledge can be used for climate adaptation strategies. The speakers discussed how TEK has been cultivated for hundreds of years, and provides profound insights into natural environments that western scientists cannot obtain. For this reason, climate solutions must respect both Indigenous knowledge and governance structures.

During this event, a rainstorm caused technical issues that forced the speakers to pause for several minutes. This interruption at first felt inconvenient, but I quickly realized that it was actually a welcome reminder of my purpose for being here, and the purpose of my research. Despite being surrounded by the Amazon rainforest, delegates and observers spend most of their time inside the convention center. It’s easy to get caught up in the politics and performance of the COP, but the storm forced me to remember the land on which I was sitting. As Indigenous groups keep reminding us, respecting what the natural world provides us is the real reason for climate action. Recognizing our connection to nature, and making room for those who understand it, is the only way we will solve the climate crisis. The moderator of this event said it better than I can: over the sound of rain pummeling the temporary roof, she called out, “you hear the rain, you hear the thunder; nature is speaking at this session.” It is time for us to listen.

COP30 brand canned water overflowing onto the street (photo by Javiera Cabezas Parra)

Sarah Lyons is a fourth-year undergraduate studying environmental sciences and political science. She is interested in environmental human rights and how the law can protect those most vulnerable to climate change. She has also worked to advance local climate policy through her internships and as the president of Students for Ecological & Environmental Development, a group that seeks to provide Northwestern students with opportunities for community service and environmental political participation. Additionally, Sarah studies environmental health as a research assistant for the Horton Research Group.

Sarah Lyons is a fourth-year undergraduate studying environmental sciences and political science. She is interested in environmental human rights and how the law can protect those most vulnerable to climate change. She has also worked to advance local climate policy through her internships and as the president of Students for Ecological & Environmental Development, a group that seeks to provide Northwestern students with opportunities for community service and environmental political participation. Additionally, Sarah studies environmental health as a research assistant for the Horton Research Group.