My Pilgrimage to Mecca in the Footsteps of the Peripatetic Saharan Islamic Scholars

By Zekeria Ahmed Salem

Associate Professor, Political Science and Program of African Studies

2024–25 Faculty Fellow, Roberta Buffett Institute for Global Affairs

Northwestern UniversityMy pilgrimage to the Muslim holy lands was inevitable. My book project, Islamic Knowledge Unbound: Mauritania and the Making of Global Islamic Authority (19th–21st Century), explores how a remote, sparsely populated West Saharan region came to produce a disproportionate number of globally influential Islamic scholars. Known for their training in the mahāẓir—desert Islamic seminaries— some of these scholars rose to prominence through itinerant teaching and scholarship both at home and across the Muslim world. I retrace their careers through manuscripts, archives, oral histories, and other sources in West Africa, the Middle East, and beyond.

My earlier findings clearly showed how the pilgrimage to Mecca, the Hajj, was often the gateway for these Saharan scholars to enter broader Islamic intellectual networks. In starting this project, I hoped to collect new data—library materials, site-specific insights, conversations, and traces of reputations left behind. But more than anything, I wanted to physically experience the path these scholars once walked and reflect on how the Hajj contributed to transforming a marginal region into a node of global Islamic authority. For all its spirituality, the Hajj is a deeply physical ordeal—six intense days in a tight, fifteen-mile circuit alongside millions of others. Before that, I spent two weeks in Medina, immersing myself in the places where my scholarly subjects lived, taught, and performed their knowledge. Many revelations came not through texts, but through the lived experience of the pilgrimage itself, which I was able to embark upon during my year as a Buffett Faculty Fellow.Medina: Living History

My journey began in Medina, the Prophet’s city, where most pilgrims stop before heading to Mecca. Though not an obligatory part of the Hajj, Medina holds immense spiritual and historical value. It is home to the Prophet’s Mosque, which today accommodates over a million worshippers at each of the five daily prayers. Despite the resistance to tomb visitation in Saudi Wahhabi doctrine, pilgrims continue to flock to the Prophet’s grave, seeking blessings.

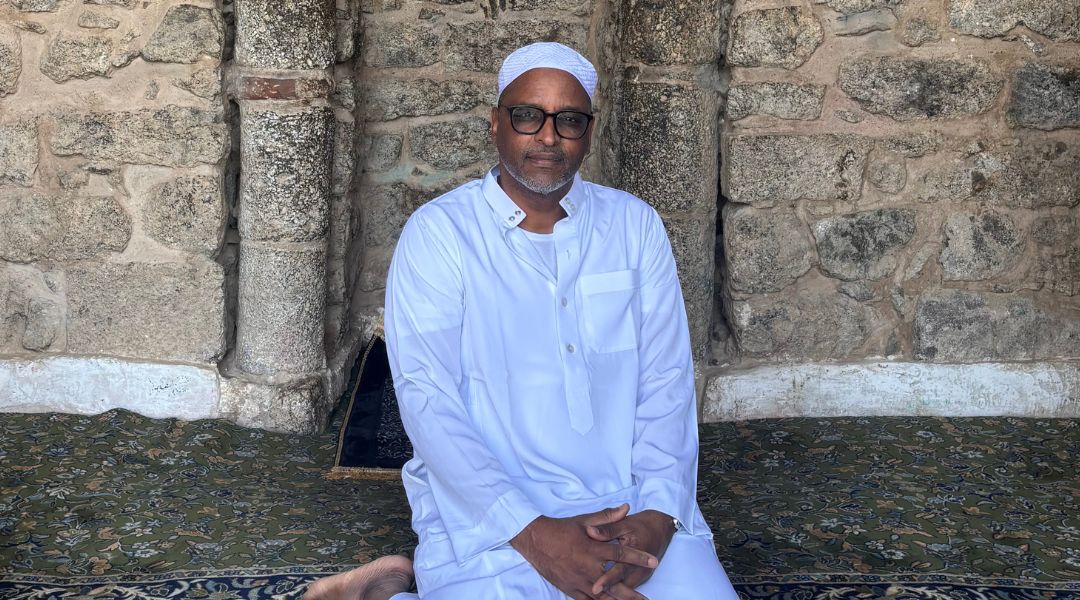

Medina's main mosque is not only a spiritual sanctuary but a vibrant intellectual hub. Between prayers, accredited scholars deliver open lessons in Qur’anic recitation, jurisprudence, theology, and more. I observed imams teaching in Arabic, Bengali, and Urdu, addressing multinational crowds. A young Senegalese Shaykh instructed Filipino and Indian pilgrims in proper reading of the Qur’an, while a Bangladeshi scholar explained Islamic law in Bengali. The global resonance of Islam was everywhere. Watching these sessions, I imagined my subjects—some perhaps seated in the same spots—building the reputations I now trace in my work.

These gatherings aren’t just ritualistic; they’re the living nodes of a global Islamic intellectual network. Many of the Saharan scholars I study began their careers in these very settings.

The Hidden Libraries of the Prophet’s Mosque

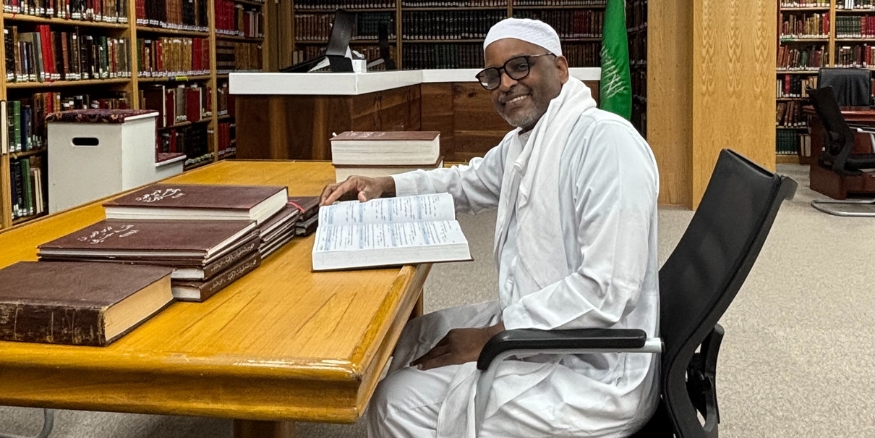

Most pilgrims never enter local libraries. I had previously visited the well-known Manuscript Library of the Prophet’s Mosque, where I had found many texts from the Saharan West. This time, I discovered by accident a much larger, 24-7 library housing over 256,000 Arabic volumes, complete with digital access, dissertation shelves, and modern infrastructure. I stumbled upon it early one morning as I wandered around the sprawling mosque compound. I had no idea such a massive library existed.

When I introduced myself as Shinqīṭī—a term synonymous with Mauritanian scholarship—the staff welcomed me warmly. They offered dates and tea at odd hours, eager to share that Mauritanian scholars were well represented in both collections. Some of their works—classical and contemporary—lined the shelves, quietly reinforcing the intellectual legacy of my homeland. These weren’t just academic visits; they felt like reunions with the voices I’d been studying for years. In Medina, scholarship is not fossilized—it breathes, teaches, greets, and persists. I had already gathered data from Qatar, the Emirates, United States, and Africa, suggesting that many Saharan/Mauritanian scholars left an indelible mark on their field and are still celebrated publicly. In the holy land, I knew I would encounter this phenomenon about at least one world famous twentieth century scholar, namely Muhammad al-Amin al-Shinqiti (d. 1973).One day, I set out to visit a newly named street honoring this towering Mauritanian scholar who, among his many accomplishments, helped establish the Islamic University of Medina in the 1960’s and rose to Saudi Arabia’s highest scholarly ranks only few years after settling there. In 2023, on the fiftieth anniversary of his death, the Saudi government launched an endowed academic chair in his name and published a 21-volume edition of his works, while also naming a street after him—a rare distinction for a foreigner in the Prophet’s city.

Initially, I couldn’t find the said street on Google Maps. With help from a curious taxi driver and online videos of the naming ceremony, I eventually located the area—under renovation and temporarily unlisted. But the surprise was profound: the street leads directly to the historic Al-Khandaq Mosque, site of the Battle of the Trench (627 CE), where the Prophet is said to have prayed during the siege. The symbolic weight was immense. It also led to the famous site of The Seven Mosques. This wasn’t just a street. The Saudi authorities clearly wanted to connect the scholarly legacy of a 20th-century Saharan, indeed African, émigré with a foundational moment in Islamic history.

Three smaller mosques bearing al-Shinqīṭī’s name were also scattered in a Medina neighborhood historically inhabited by the Shanāqiṭa—Mauritanians who settled here as early as the 17th century.

Mecca: Reliving History

In Mecca, the Holy Mosque also has a library—but its main branch has moved fifteen miles away. There, in an eight-story building, I found printed books, periodicals, and family archives, including several works by Mauritanian scholars. It was a treasure trove, though overwhelming. I realized I would need to return in the future to do this material justice. For now, I had what I needed: copies of rare manuscripts, new editions of collected works of some of my subjects, thesis on their works etc. Though unrelated to my project, other unexpected discoveries continued. One day, my taxi driver missed the hotel exit, taking me through a neighborhood where African countries host their pilgrims. I travelled mostly among Mauritanians and learnt a lot from many of them, but here I passed a hotel flying the Chadian flag, street vendors from Nigeria, and even a building labeled “Katsina State Islamic Authority.” The African presence at the Hajj is vibrant and visible through flags, dress, and language. In the throngs circling the Kaʿbah, national identities are worn like uniforms. Another surprising feature: the mixing of men and women during the rituals. Despite Western stereotypes, the physical segregation of gender so often associated with Islam— and virtually impossible in the Hajj given the crowding during the performance of mandatory rituals—is utterly nonexistent here.

For three weeks, I lived within people, texts, sites, and legacies I’ve spent years researching. Somewhere between the marble floors of the Prophet’s Mosque and the majestic Kaʿbah—the sacred house of God—I realized I wasn’t just researching the legacy of Saharan scholars in the holy lands—I was reliving their journey. The libraries, streets, mosques, and conversations brought their stories to life in ways no archive ever could. Their global journeys began with the Hajj, and in walking that path, I glimpsed the forces—both spiritual and scholarly—that made many of them aware of the size or the wider Muslim community and how they could contribute to its intellectual life and religious guidance beyond the borders of their remote Saharan homeland. My pilgrimage was not just about completing a religious duty or gathering new data. It was about witnessing how knowledge travels, how religious authority is built, and how the ill-named “margins of the Muslim world”—like Mauritania—sought with some degree of success to recenter themselves.